All the stuff, I’ve been hoarding over the past year for the newsletter.

Ryan Holiday’s 100 (Short) Rules for a Better Life

4 - Say no (a lot).

15 - It’s not about routine but about practices.

71 - Go the f*ck to sleep.

81 - Don’t just read books, re-read books.

Maria Popova, on How Reading Is Like Love

Now you are being read.

Your body is being subjected to a systematic reading, through channels of tactile information, visual, olfactory, and not without some intervention of the taste buds. Hearing also has its role, alert to your gasps and your trills. It is not only the body that is, in you, the object of reading: the body matters insofar as it is part of a complex of elaborate elements, not all visible and not all present, but manifested in visible and present events: the clouding of your eyes, your laughing, the words you speak, your way of gathering and spreading your hair, your initiatives and your reticences, and all the signs that are on the frontier between you and usage and habits and memory and prehistory and fashion, all codes, all the poor alphabets by which one human being believes at certain moments that he is reading another human being…

Shane Parrish posits Your Thinking Rate Is Fixed

A good metaphor is installing an update to the operating system on your laptop.

Would you rather install an update that fixes bugs and improves existing processes, or one that just makes everything run faster? Obviously, you’d prefer the former. The latter would just lead to more crashes. The same is true for updating your mental operating system.

Ryan Holiday presents A Practical Philosophy Reading List: A Few Books You Can Actually Use in Real Life

You must know by now: I don’t believe that philosophy is something for the classroom.

It’s something that helps you with life.

It shouldn’t be complicated.

It shouldn’t be confusing.

It should be clear, and it should be usable.

As Epicurus put it, “Vain is the word of the philosopher which does not heal the suffering of man.”

Leo Babauta on the First Two Steps to Creating Resilience

The first step is to remove things that are adding unnecessary stress.

The second step is to do things that help us feel replenished.

David Ogilvy had skin in the game! Who knew?

The Ogilvy agency … was founded by a man who didn’t have an MBA, or even a college degree.

Before he became the King of Madison Avenue, Englishman David Ogilvy was an Oxford dropout who worked as a chef in Paris, a door-to-door salesman, a researcher for George Gallup, an agent of the British Intelligence Service during WWII, and a farmer in Pennsylvania.In fact, while most agencies had subordinates present campaign ideas to clients, Ogilvy often made these presentations himself; he wanted to be directly involved, and felt it made the pitches more memorable (“One orchestra looks like every other orchestra, but there is no confusing one conductor with another”).

Ogilvy also rejected around 60 potential new clients each year. A common reason for this rejection was the chairman’s lack of confidence in the product that a company wanted his agency to pitch. Ogilvy used all the products he advertised, and wouldn’t create campaigns for those he couldn’t personally back, believing that it was “flagrantly dishonest for an advertising agent to urge consumers to buy a product which he would not allow his own wife to buy,” and that it was impossible to craft an effective ad for something you couldn’t earnestly get behind …

The beauty of Seth Godin¸ is that every post on his is darn here quotable. This is him, on the weight of repetitive tasks …

If we’re lucky enough to work indoors, with free snacks and podcasts in the background, we might not get physically exhausted the way we would moving thousands of pounds of bricks. But the cognitive and emotional toll of repetitive tasks is real, even if doesn’t leave callouses.

The discipline is to invest one time in getting your workflow right instead of paying a penalty for poor digital hygiene every single day.

Hacking your way through something “for now” belies your commitment to your work and your posture as a professional. Get the flow right, as if you were hauling bricks.

The Art of Manliness podcast have a ton of episodes on making and breaking habits, which they have collected into one handy page

If you’ve failed at habit building or breaking in the past, you might think you just need more willpower.

That’s not what James Clear argues in this interview. Rather, it’s simply about crafting optimal systems for behavior change. Clear walks the listener through his own research-backed 4-step process for effective habit formation.

What is the key to making risky decisions? Scott H Young has thoughts

The correct approach to thinking about risky decisions is not to ignore the odds, but to model your decision and explicitly include things like the benefits to coming in second place.

A good decision model ought to include:

- What is the baseline likelihood of success?

- What information do you have that makes you different from the average competitor?

- What are the outcomes for less-than-ideal results?

- What are the emotional and financial costs of going forward?

Leo Babauta on Staying at the Edge of Uncertainty

When we get into a situation that feels uncertain, most of us will immediately try to get to a place of certainty.

Instead of having a difficult conversation, we’ll stay in a crappy situation for longer than we need to.

Instead of putting our art out into the world, we’ll hide it in the safety of obscurity.

When things feel chaotic and overwhelming, we look for a system that will feel ordered and simple.All of us do this in most areas of our lives. Sometimes, we are able to voluntarily stay in uncertainty, but those times are relatively rare, and usually we don’t like it so much.

Here’s the thing: the edge of uncertainty and chaos is where we learn, grow, create, lead, make incredible art and new inventions.

The edge of uncertainty is where we explore, go on adventures, get curious, and reinvent ourselves.

The edge of uncertainty is where we can find unexpected beauty, love, intimacy, vulnerability, meaning.

Everything we truly crave is at the edge of uncertainty, but we run from it.The trick is to stay in it.

You’ve read the classic works of stoicism. What now? The Daily Stoic helps with, Assembling A “Bible” of Stoicism: What To Read After The Romans, https://dailystoic.com/bible-of-stoicism

The world in which a man lives shapes itself chiefly by the way in which he looks at it, and so it proves different to different men; to one it is barren, dull, and superficial; to another rich, interesting, and full of meaning. On hearing of the interesting events which have happened in the course of a man’s experience, many people will wish that similar things had happened in their lives too, completely forgetting that they should be envious rather of the mental aptitude which lent those events the significance they possess when he describes them. . . . All the pride and pleasure of the world, mirrored in the dull consciousness of a fool, are poor indeed compared with the imagination of Cervantes writing his Don Quixote in a miserable prison.

—Schopenhauer, The Wisdom of Life (1851)

P.S. If you are new and want to explore the Stoic way of thinking about life, I heartily recommend Ryan Holiday’s trilogy for a gentle introduction. The Obstacle is the Way, Ego is the Enemy and Stillness is the key are short yet surprisingly deep and engaging books.

Speaking of reading, Ali Abdaal teaches us, The Art of Reading More Effectively and Efficiently

Level 4: Syntopical Reading

The final level of reading is about our understanding of a subject more generally. Whereas analytical reading focuses on our comprehension of a specific book, syntopical reading helps shape our opinion and increase our overall fluency of the wider topic through understanding how different books relate to one another. This may sound a little abstract, but bear with me.“The benefits [of syntopical reading] are so great that it is well worth the trouble of learning how to do it” — Adler

The first step is to begin by deciding the subject we want to tackle (eg: productivity or habit-formation). We can then draw up a bibliography of books on the topic, and select just a handful of them that we believe to be most relevant.

Having compiled the list of books, we can begin reading syntopically. This means reading each of the books analytically and building mental connections between each of them. I try to define common subject keywords in my own words, identify and answer the most pressing questions that the books collectively address, and make an informed decision about the strengths of each author’s argument.

“Creativity is just connecting things” — Steve Jobs

Through syntopical reading we’re connecting the best ideas on a subject, which acts as a powerful catalyst giving rise to creative solutions and real insight. It’s truly game-changing (when we actually do it).

Shane Parrish distills Mortimer Adler’s advice from How to Read a Book: The Ultimate Guide by Mortimer Adler

I bet you already know how to read a book. You were taught in elementary school.

But do you know how to read well?

There is a difference between reading for understanding and reading for information.

If you’re like most people, you probably haven’t given much thought to how you read. And how you read makes a massive difference to knowledge accumulation.

A lot of people confuse knowing the name of something with understanding. While great for exercising your memory, the regurgitation of facts without solid understanding and context gains you little in the real world.

A useful heuristic: Anything easily digested is reading for information.

Consider the newspaper, are you truly learning anything new? Do you consider the writer your superior when it comes to knowledge in the subject? Odds are probably not. That means you’re reading for information. It means you’re likely to parrot an opinion that isn’t yours as if you had done the work.

This is how most people read. But most people aren’t really learning anything new. It’s not going to give you an edge, make you better at your job, or allow you to avoid problems.“Marking a book is literally an experience of your differences or agreements with the author. It is the highest respect you can pay him.”

— Edgar Allen PoeLearning something insightful requires mental work.

It’s uncomfortable. If it doesn’t hurt, you’re not learning.

You need to find writers who are more knowledgeable on a particular subject than yourself. By narrowing the gap between the author and yourself, you get smarter.

Farnam Street has an awesome page chockful of articles, that help us become better readers

You can’t get where you want to go if you’re not learning all the time. One of the best ways to learn is to read.

Reading habits don’t need to be complicated, you can start a simple 25 page a day habit right now. While it seems small the gains add up quickly.

Above all else remember that just because you’ve read something doesn’t mean you’ve done the work required to have an opinion.

Ryan Holiday on Marginalia, the Anti-Library, and Other Ways to Master the Lost Art of Reading

Step three, be ruthless about acquiring knowledge through books. If you see anything that remotely intrigues you–just get it.

Quit books that don’t hold your interest or deliver the goods.

Swarm onto topics that do, even if there is no immediate relevancy to what you’re doing. After all, creativity comes from combining old ideas into something new. Reading a variety of topics gives you more ammo than your competition.If something enthralls you and you want to deeply understand it, go at it. You don’t have to slowly trudge along through a book. Think of someone like Frederick Douglass, who brought himself up out of slavery by sneaking out and teaching himself to read, or Richard Wright who forged notes from his white boss so he could check out books from the library. Books weren’t some idle pursuit or pastime for these great individuals, they were survival itself.

Ed Latimore on How to stop hating someone and holding grudges

You don’t stop hating someone because it’s the right thing to do or because they’ve done something to finally make it acceptable for you to stop hating the person. You stop hating because if you don’t stop, then there are very consequences to your mental, physical, and emotional health.

You’re the only who pays the cost and you get absolutely nothing of value in return. In fact, when you hate someone, you’re paying this cost to have things of value taken from you. Mainly, your peace of mind, love of other people, and openness to the world.

This is why releasing and removing hatred is an important goal.

Ryan Holiday on How to Digest Books Above Your “Level”

I shouldn’t be able to read most of the books on my shelf. I never took a single classical history class and I cheated through most of Economics 001. Still, the loci of my library are Greek History and Applied Economics. And though they often are beyond me educationally, I’m able to comprehend them because of some equalizing tricks. Reading to lead or learn requires that you treat your brain like the muscle that it is–lifting the subjects with the most tension and weight. For me, that means pushing ahead into subjects you’re not familiar with and wresting with them until you can–shying away from the “easy read.”

This is how I break down a new book: …

Ryan Holiday on How To Read More — A Lot More

When you read a lot of books people inevitably assume you speed read. In fact, that’s probably the most common email I get. They want to know my trick for reading so fast. They see all the books I recommend every month in my reading newsletter and assume I must have some secret. So they ask me to teach them how to speed read.

That’s when I tell them I don’t have a secret. Even though I read hundreds of books every single year, I actually read quite slow. In fact, I read deliberately slow, so that I can take notes (and then whenever I finish a book, I go back through and transcribe these notes for my version of a commonplace book.

So where do I get the time?

Look, where do you get the time to eat three meals a day? How do you have time to do all that sleeping? How do you manage to spend all those hours with your kids or wife or a girlfriend or boyfriend?

You don’t get that time anywhere, do you? You just make it because it’s really important. It’s a non-negotiable part of your life.

Ryan Holiday on How And Why To Keep A “Commonplace Book”

This is why I have the Commonplace Blog too! And also why, I am now creating a Zettelkasten to help me think and write.

Some of the greatest men and women in history have kept these books. Marcus Aurelius kept one–which more or less became the Meditations. Petrarch kept one. Montaigne, who invented the essay, kept a handwritten compilation of sayings, maxims and quotations from literature and history that he felt were important. His earliest essays were little more than compilations of these thoughts. Thomas Jefferson kept one. Napoleon kept one. HL Mencken, who did so much for the English language, as his biographer put it, “methodically filled notebooks with incidents, recording straps of dialog and slang” and favorite bits from newspaper columns he liked. Bill Gates keeps one.

… And if you still need a why–I’ll let this quote from Seneca answer it (which I got from my own reading and notes):

“We should hunt out the helpful pieces of teaching and the spirited and noble-minded sayings which are capable of immediate practical application–not far far-fetched or archaic expressions or extravagant metaphors and figures of speech–and learn them so well that words become works.”

Book I’m reading - The Code Breaker, lovely article on Ars Technica

You were in the middle of reporting this book when something seismic happened in the world of CRISPR. In 2018, a Chinese scientist named He Jiankui revealed he had not only edited human embryos but started pregnancies with them, leading to the birth of twin girls. How did that affect the trajectory of the story you were trying to tell?

That really became a crucial turning point in the narrative. Because now all these scientists were forced to wrestle with the moral implications of what they’d helped create. But then things changed again when the coronavirus struck. I wound up working on the book for another year to watch the players as they took on this pandemic. And that actually caused my own thinking about CRISPR to evolve.

How so?

I think I felt a visceral resistance at times to the notion that we could edit the human genome, especially in ways that would be inheritable. But that changed both for me and for Doudna as we met more and more people who are themselves afflicted by horrible genetic problems or who have children who are suffering from them. And when our species got slammed by a deadly virus, it made me more open to the idea that we should use whatever talents we have in order to thrive and be healthy. So I’m now even more open to gene editing done for medical purposes, whether that’s sickle cell anemia, or Huntington’s, or Tay-Sachs, or even to increase our resistance to viruses and other pathogens and to cancer.

I still have worries. One is I don’t want gene editing to be something only the rich can afford and it leads to encoding inequalities into our societies. And, secondly, I want to make sure we don’t reduce the wonderful diversity that exists within the human species.

Annual Letters, from folks I listen to and learn from …

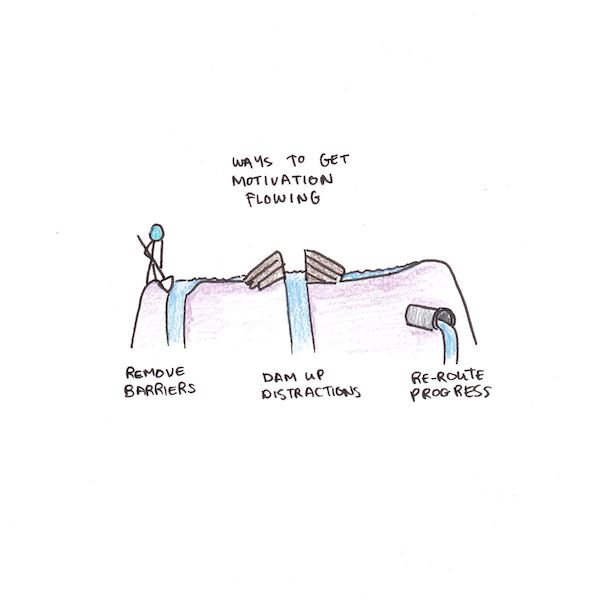

The Neuroscience of Motivation

When the Eiffel Tower was a Parisian Startup Laboratory

During the pandemic, the Eiffel Tower has been undergoing a fresh paint job ahead of the 2024 Olympics that harkens back to its golden hue of the early 20th century. But at that time, the Eiffel Tower was more than just an attraction: Gustave Eiffel was using his new tower as a his personal laboratory of scientific innovation. In 1909, Eiffel built its first wind tunnel at the foot of the tower, which was made available to the earliest pioneers in aviation and aircraft design. The wind tunnel, still in service in Paris, inside “the oldest aeronautical test laboratory still in working order,” can be considered one of Eiffel’s littlest-known monuments.

Why We Struggle to Motivate Ourselves

While it’s easy to think about pain in the most dramatic terms, it’s often the small pinches and itches that really derail progress.

How many people fail to set up retirement accounts because the thought of trying to understand their 401k program makes them feel a bit anxious? How many get stuck in dead-end jobs because the thought of reaching out to talk to a few people in different career spaces feels awkward?

How to Improve Your Self-Awareness

Self-awareness comes from building a richer, more accurate model of yourself. This combines not only theory, but experience.

Having more self-awareness leads, straightforwardly to more success. If you understand how you operate, both as an individual and as a human being generally, you can be more successful with your ambitions.

But the benefit of self-awareness is much deeper than this. Understanding yourself transcends just trying to make more money or have a better job, because it helps you realize why you want to pursue those things in the first place. In some places, this will strengthen your ambitions, as you recognize a deeper purpose to your goals, in other cases it may change what you pursue entirely, leaving some pursuits that you recognize won’t actually make you fulfilled.

Here’s 10,000 Hours. Don’t Spend It All in One Place.

On October 20, 1874, in Danbury, Connecticut, a child was born who would grow up to be one of the greatest American composers of classical music. More than a half-century ahead of his time, he combined late romanticism, American folk, and avant-garde techniques in a way that revolutionized music.

On the very same day, in the same town, a child was born who would grow up to transform the business of financial planning. An actuary, successful insurance entrepreneur, and well-known financial author, he devised ingenious life-insurance products and created the modern practice of estate planning.It was not a coincidence that the great composer and the celebrated financial innovator shared a birthday and birthplace. They were the same man: Charles Edward Ives.

There’s an old proverb that goes, “Duos qui sequitur lepores neutrum capit”—“He who follows two hares catches neither.” Perhaps that’s so, but he who chases two hares can at least have a great time trying, which can be more important in a good life. Many of my graduate students in public policy and business administration have a strong background and interest in subjects unrelated to their academic discipline. My advice to them, based on the truths above, is to not abandon either one.

The interests don’t have to be alike. After all, Ives didn’t catch two hares—it was more like a dolphin and a rhinoceros.

A Crash Course in Real World Self-Defense

#1. Use your brain and walking shoes first. Most of the time, you can avoid fights altogether if you just keep a cool head. Keep in mind that any fight can potentially put someone in the hospital or worse; to that end, walking away or using words to deescalate the conflict is often the best defense. So when you make the choice to engage in combat, ask yourself if it’s worth it. Even if you manage to come out on top, you could be looking at heavy legal fines, or the guilt of knowing you caused another person long-term injury, so it’s best to walk away whenever possible. Even better yet is to avoid environments that can put you in antagonistic situations in the first place, such as parties or bars where there might be excessive consumption of alcohol. To repeat the old adage, “Discretion is the better part of valor.”

#7. Keep it simple. “Okay, first, your opponent grabs your lapel. Turn your hand. Now grab his wrist with both your hands. Next turn away from him, pivoting on the balls of your feet. After that you’re going to step under his elbow, pull his arm, then shift your body weight so that he’s moving towards you. Now catch his head with your calf muscle and . . .” Have you ever seen someone teach this sort of complex technique? Such maneuvers tend to not work so well, and that’s largely because they’re too complicated. A joint lock or hold that’s too complicated causes problems for two reasons. First, if any “link” in the chain of moves is weak, then the entire technique can fail. When you factor in the different body sizes and levels of strength that you’re likely to encounter, it adds yet another variable. Second, it requires too much memory and concentration, and when you’re in a fight, those are two things that won’t come easy to you. In short, complicated techniques usually aren’t worth your time, at least in the context of a street fight. The more simple and boring a technique is, the more reliable it tends to be. Let’s rewrite that complicated technique above to make it more simple: “Punch the guy in the face until he lets go, then run.” Much easier to remember, right?

Mandy Brown asking Remote to Who?

If remote work gives us anything at all, it gives us the chance to root ourselves in a place that isn’t the workplace. It gives us the chance to really live in whatever place we have chosen to live—to live as neighbors and caretakers and organizers, to stop hoarding all of our creative and intellectual capacity for our employers and instead turn some of it towards building real political power in our communities.

This Is How To Have A Long Awesome Life: 5 Secrets From Research

If you ever wanted to be guilted in a very happy and helpful way, into exercising, then Eric Barker is here to do just that

Daniel Lieberman decided to do an informal — and very sneaky — study.

While at an academic conference, he counted how many people took the escalator vs the stairs. In ten minutes, 151 people walked past him and only 11 used the stairs. That’s just 7 percent.

Thing was, this was a meeting of the American College of Sports Medicine.

And the name of the conference was “Exercise Is Medicine.”

Actually, these results weren’t as bad as you might think — formal studies of the general populace show, on average, only 5% of people take the stairs. We all know exercise is good… but most of us just don’t do it.

Farnam Street has a concise summary of the evergreen classic, How to Win Friends and Influence People.

I shan’t summarise it here. A summary of a summary would be redonkulous, non? 😂

Go Read.

Ok, one quote that always resonates with me.

If there is any one secret of success, it lies in the ability to get the other person’s point of view and see things from that person’s angle as well as from your own.

Carnegie was echoing Maimonides of old. Munger too, later echoed Carnegie when he spoke of the work required to have an opinion

“The ability to destroy your ideas rapidly instead of slowly when the occasion is right is one of the most valuable things.

You have to work hard on it.

Ask yourself what are the arguments on the other side.

It’s bad to have an opinion you’re proud of if you can’t state the arguments for the other side better than your opponents.

This is a great mental discipline.”

The World Map of the Internet in 2021

I was going to send this to the work newsletter, but the drawings are too gorgeous to restrict to just that subset.

There’s all sorts of stuff; protocols that undergird the net, browsers in use, & how the world is slowly amalgamating into huge walled continents of a few centralised websites.

These maps are a joy to watch. (and a bit unsettling to reflect on.)

Reminds me a little bit of this map of food corporates.

Maya Angelou’s Paris Review Interview, on writing and language and life and growing up. Watching this could probably the best hour of your life.

On Making it Look Easy …

I try to pull the language into such a sharpness that it jumps off the page. It must look easy, but it takes me forever to get it to look so easy. Of course, there are those critics — New York critics as a rule — who say, Well, Maya Angelou has a new book out and of course it’s good but then she’s a natural writer. Those are the ones I want to grab by the throat and wrestle to the floor because it takes me forever to get it to sing. I work at the language.

On Wisdom …

“Most people don’t grow up.

It’s too damn difficult.What happens is most people get older. That’s the truth of it. They honor their credit cards, they find parking spaces, they marry, they have the nerve to have children, but they don’t grow up.

Not really. They get older.But to grow up costs the earth, the earth. It means you take responsibility for the time you take up, for the space you occupy. It’s serious business. And you find out what it costs us to love and to lose, to dare and to fail. And maybe even more, to succeed.”

P.S. Subscribe to my mailing list!

Forward these posts and letters to your friends and get them to subscribe!

P.P.S. Feed my insatiable reading habit.