When a book keeps popping up in your radar, from a wide variety of sources, over months, then you just have to go read it.

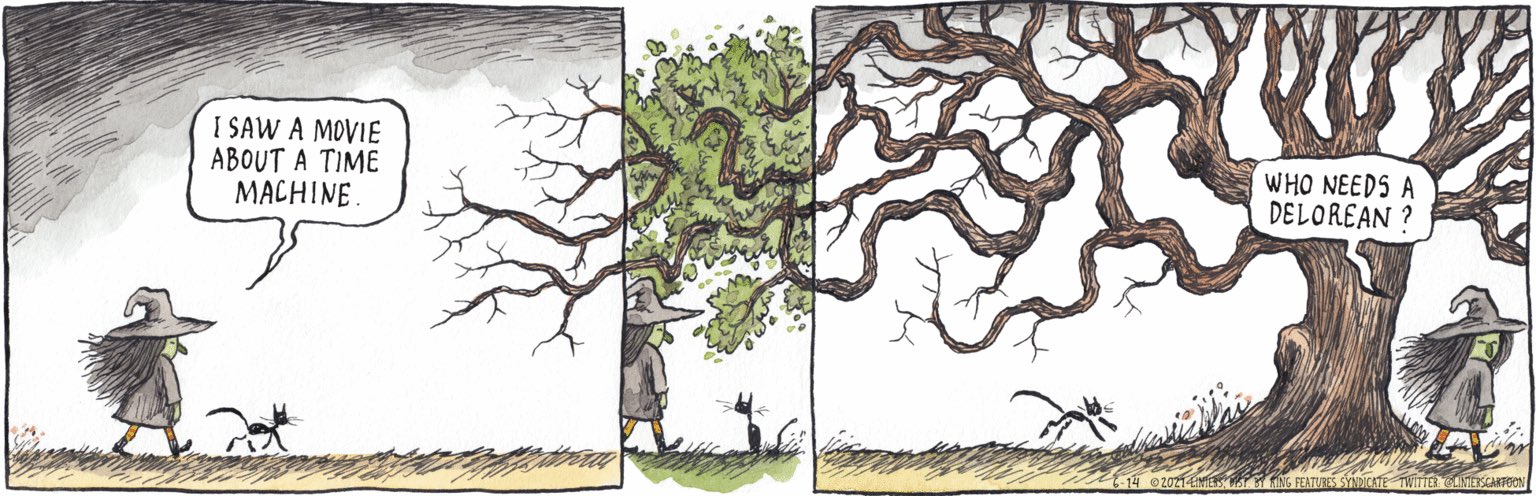

via the amazing Ricardo Siri. click the image to see full size.

The Overstory was it for me.

Two friends, three random youtube videos and a couple of podcasts made be buckle down and read it.

I wanted to go slow and savour it and finish it slowly. But I got greedy and gobbled it down yesterday.

This one is for the Lindy List.

The book’s about a set of characters and trees and about the intersections and interleaving of their lives with each other and with trees.

It’s a love letter to trees.

Or maybe it’s a love letter from Aberewaa, from Atira, from Bhoomi, from Gaia to us.

My highlights from the book follow …

The greatest delight which the fields and woods minister, is the suggestion of an occult relation between man and the vegetable. I am not alone and unacknowledged. They nod to me, and I to them. The waving of the boughs in the storm, is new to me and old. It takes me by surprise, and yet is not unknown. Its effect is like that of a higher thought or a better emotion coming over me, when I deemed I was thinking justly or doing right.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

Earth may be alive: not as the ancients saw her—a sentient Goddess with a purpose and foresight—but alive like a tree. A tree that quietly exists, never moving except to sway in the wind, yet endlessly conversing with the sunlight and the soil. Using sunlight and water and nutrient minerals to grow and change. But all done so imperceptibly, that to me the old oak tree on the green is the same as it was when I was a child.

—James Lovelock

Tree . . . he watching you. You look at tree, he listen to you. He got no finger, he can’t speak. But that leaf . . . he pumping, growing, growing in the night. While you sleeping you dream something. Tree and grass same thing.

—Bill Neidjie

Before the people at the customer service desk even hand her the phone, she knows. And all the way home to Illinois she thinks:

How do I recognize this already? Why does this all feel so much like remembering?

United, the trio sit together one last time. They have no explanation. There never will be one. The least likely person in the world has gone on an impossible tour without them. In place of explanation, memory. They put their hands on each other’s shoulders and tell each other stories of how things were.

The judges award him no medal—not even a bronze. They say it’s because he has no bibliography. A bibliography is a required part of the formal report. Adam knows the real reason. They think he stole. They can’t believe a kid worked for months on an original idea, for no reason at all except the pleasure of looking until you see something.

Humans carry around legacy behaviors and biases, jerry-rigged holdovers from earlier stages of evolution that follow their own obsolete rules. What seem like erratic, irrational choices are, in fact, strategies created long ago for solving other kinds of problems. We’re all trapped in the bodies of sly, social-climbing opportunists shaped to survive the savanna by policing each other.

“Kindness may look for something in return, but that doesn’t make it any less kind.”

If you want a person to help you, convince them that they’ve already helped you beyond saying. People will work hard to protect their legacy.

Why? She says no reason. A lark. A whim. Freedom. But there is, of course, no freedom. There are only ancient prophecies that scry the seeds of time and say which will grow and which will not.

… each night, Ray has almost forever to think: Something is happening to me. Something heavy, huge, and slow, coming from far outside, that I do not understand. He has no idea. The thing that comes for him is a genus more than six hundred species strong. Familiar, protean, setting up camp from the tropics all the way up through the temperate north: the generalist emblem of all trees. Thick, clotted, craggy, but solid on the earth, and covered in other living things. Three hundred years growing, three hundred years holding, three hundred years dying. Oak.

You have given me a thing I could never have imagined, before I knew you. It’s like I had the word “book,” and you put one in my hands. I had the word “game,” and you taught me how to play. I had the word “life,” and then you came along and said, “Oh! You mean this.”

In fact, it’s Douggie’s growing conviction that the greatest flaw of the species is its overwhelming tendency to mistake agreement for truth. Single biggest influence on what a body will or won’t believe is what nearby bodies broadcast over the public band. Get three people in the room and they’ll decide that the law of gravity is evil and should be rescinded because one of their uncles got shit-faced and fell off the roof.

Her trees are far more social than even Patricia suspected. There are no individuals. There aren’t even separate species. Everything in the forest is the forest. Competition is not separable from endless flavors of cooperation. Trees fight no more than do the leaves on a single tree. It seems most of nature isn’t red in tooth and claw, after all. For one, those species at the base of the living pyramid have neither teeth nor talons. But if trees share their storehouses, then every drop of red must float on a sea of green.

With them, Dad may throw softballs and tell bubble-gum wrapper jokes and play tag. But he reserves his best gifts for his little plant-girl, Patty.

Their closeness bothers her mother. “I ask you. Has there ever been such a little nation of two?”

They drive through a land once covered in dark beech forest. “Best tree you could ever want to see.” Strong and wide but full of grace, flaring out nobly at the base, into its own plinth. Generous with nuts that feed all comers. Its smooth, white-gray trunk more like stone than wood. The parchment-colored leaves riding out the winter—marcescent, he tells her—shining out against the neighboring bare hardwoods. Elegant with sturdy boughs so much like human arms, lifting upward at the tips like hands proffering. Hazy and pale in spring, but in autumn its flat, wide sprays bathe the air in gold.

“What happened to them?” The girl’s words thicken when sadness weighs them down.

“We did.”

“If you see a trunk carved full of letters, it’s a beech. People can’t help writing all over that smooth gray surface. God love ’em. They want to watch their lettered hearts growing bigger, year after year.

Fond lovers, cruel as their flame, cut in these trees their mistress’ name. Little, alas, they know or heed how far these beauties hers exceed!”

He tells her how the word beech becomes the word book, in language after language. How book branched up out of beech roots, way back in the parent tongue. How beech bark played host to the earliest Sanskrit letters. Patty pictures their tiny seed growing up to be covered with words.

On her fourteenth birthday, he gives her a bowdlerized translation of Ovid’s Metamorphosis. Patricia opens the book to the first sentence and reads:

Let me sing to you now, about how people turn into other things.

At the funeral, Patty reads from Ovid. The promotion of Baucis and Philemon to trees. Her brothers think she has lost her mind with grief.

She won’t let her mother throw anything out. She keeps his walking stick and porkpie hat in a kind of shrine. She preserves his precious library—Aldo Leopold, John Muir, his botany texts, the Ag Extension pamphlets he helped to write. She finds his copy of adult Ovid, marked all over, as people mark beeches. The underscores start, triple, on the very first line:

Let me sing to you now, about how people turn into other things.

She replants their experiment in a spot behind the house where she and her father liked to sit on summer nights and listen to what other people called silence. She remembers what he told her about the species. People, God love ’em, must write all over beeches. But some people—some fathers—are written all over by trees.

Late at night, too tired from teaching and research to work more, she reads her beloved Muir. … She writes her favorite lines in the inside covers of her field notebooks and peeks at them when department politics and the cruelty of frightened humans get her down. The words withstand the full brutality of day.

We all travel the Milky Way together, trees and men. . . . In every walk with nature one receives far more than he seeks. The clearest way into the universe is through a forest wilderness.

It’s a miracle, she tells her students, photosynthesis: a feat of chemical engineering underpinning creation’s entire cathedral. All the razzmatazz of life on Earth is a free-rider on that mind-boggling magic act. The secret of life: plants eat light and air and water, and the stored energy goes on to make and do all things. She leads her charges into the inner sanctum of the mystery: Hundreds of chlorophyll molecules assemble into antennae complexes. Countless such antennae arrays form up into thylakoid discs. Stacks of these discs align in a single chloroplast. Up to a hundred such solar power factories power a single plant cell. Millions of cells may shape a single leaf. A million leaves rustle in a single glorious ginkgo.

Too many zeros: their eyes glaze over. She must shepherd them back over that ultrafine line between numbness and awe. “Billions of years ago, a single, fluke, self-copying cell learned how to turn a barren ball of poison gas and volcanic slag into this peopled garden. And everything you hope, fear, and love became possible.” They think she’s nuts, and that’s fine with her. She’s content to post a memory forward to their distant futures, futures that will depend on the inscrutable generosity of green things.

Years from now, she’ll write a book of her own, The Secret Forest. Its opening page will read:

You and the tree in your backyard come from a common ancestor. A billion and a half years ago, the two of you parted ways. But even now, after an immense journey in separate directions, that tree and you still share a quarter of your genes. . . .

She addresses the cedar, using words of the forest’s first humans. “Long Life Maker. I’m here. Down here.” She feels foolish, at first. But each word is a little easier than the next.

“Thank you for the baskets and the boxes. Thank you for the capes and hats and skirts. Thank you for the cradles. The beds. The diapers. Canoes. Paddles, harpoons, and nets. Poles, logs, posts. The rot-proof shakes and shingles. The kindling that will always light.”

Each new item is release and relief. Finding no good reason to quit now, she lets the gratitude spill out. “Thank you for the tools. The chests. The decking. The clothes closets. The paneling. I forget. . . . Thank you,” she says, following the ancient formula. “For all these gifts that you have given.” And still not knowing how to stop, she adds, “We’re sorry. We didn’t know how hard it is for you to grow back.”

She takes his shaking hand in the dark. It feels good, like a root must feel, when it finds, after centuries, another root to pleach to underground. There are a hundred thousand species of love, separately invented, each more ingenious than the last, and every one of them keeps making things.

places remember what people forget.

She always thought he was just myth. She must still discover that myths are basic truths twisted into mnemonics, instructions posted from the past, memories waiting to become predictions.

moss-swarmed floor—straight up, with no taper, like a russet, leathery apotheosis.

The spruces near the cabin wave spooky prophecies under the near-full moon. There’s a straight line of them, the memory of a vanished fence where red crossbills once liked to sit and shit out seeds. The trees are busy tonight, fixing carbon in their dark phase. All will be in flower before long: huckleberry and currant, showy milkweed, tall Oregon grape, yarrow and checkermallow. She marvels again at how the planet’s supreme intelligence could discover calculus and the universal laws of gravitation before anyone knew what a flower was for.

They read The Secret Forest again. It’s like a yew: more revealing on a second look. They read about how a branch knows when to branch. How a root finds water, even water in a sealed pipe. How an oak may have five hundred million root tips that turn away from competition. How crown-shy leaves leave a gap between themselves and their neighbors. How trees see color. They read about the wild stock market trading in handicrafts, aboveground and below. About the complex limited partnerships with other kinds of life. The ingenious designs that loft seeds in the air for hundreds of miles. The tricks of propagation worked upon unsuspecting mobile things tens of millions of years younger than the trees. The bribes for animals who think they’re getting lunch for free.

They read about myrrh-tree transplanting expeditions depicted in the reliefs at Karnak, three thousand five hundred years ago. They read about trees that migrate. Trees that remember the past and predict the future. Trees that harmonize their fruiting and nutting into sprawling choruses. Trees that bomb the ground so only their own young can grow. Trees that summon air forces of insects to come save them. Trees with hollowed trunks wide enough to hold the population of small hamlets. Leaves with fur on the undersides. Thinned petioles that solve the wind. The rim of life around a pillar of dead history, each new coat as thick as the maker season is generous.

No one sees trees. We see fruit, we see nuts, we see wood, we see shade. We see ornaments or pretty fall foliage. Obstacles blocking the road or wrecking the ski slope. Dark, threatening places that must be cleared. We see branches about to crush our roof. We see a cash crop. But trees—trees are invisible.

Trees know when we’re close by. The chemistry of their roots and the perfumes their leaves pump out change when we’re near. . . . When you feel good after a walk in the woods, it may be that certain species are bribing you. So many wonder drugs have come from trees, and we haven’t yet scratched the surface of the offerings. Trees have long been trying to reach us. But they speak on frequencies too low for people to hear.

What you make from a tree should be at least as miraculous as what you cut down.

Tonight’s poem is Chinese—Wang Wei—twelve hundred years old, from an anthology of poetry she winds through at random, the way she likes to hike:

I know no good way

to live and I can’t

stop getting lost in my

thoughts, my ancient forests. . . .You ask: how does a man rise or fall in this life?

The fisherman’s song flows deep under the river.

Then the river is running over her, and she’s done. She douses the dim, low-watt bulb clipped to the headboard. All that’s left her is the moon. She rolls on her side and curls up, her face pressed into the dank pillow. After a minute, the end of her mouth pulls into an abiding smile.

“I did not almost forget. Good night.”

Good night.

P.S. Subscribe to my mailing list!

Forward these posts and letters to your friends and get them to subscribe!

P.P.S. Feed my insatiable reading habit.